“Oh, Glory 2” – James Dargan, Baritone; Mark Whitlock, Piano

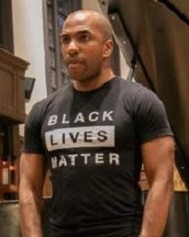

James Dargan, frequently on our stage as a bass soloist, presented for us a unique livestream recital especially tailored to this important moment in our lives. Read about his program “Oh, Glory” as described in the 2/15/20 Worcester Telegram to get a preview of his powerful and relevant musical performances blending Black history and music. In James’ own words: “While the first “Oh, Glory” was all about showing the silliness of musical and racial boxes, “OG2” is all about exploring the different facets within the ‘box’ of Black composers, and the differing viewpoints on Blackness in the poetry they set to music. I hope that the complexity and variety of these songs shows that again, boxes are silly, in music and in life. I invite my audience to explore and break free along with me.”

In lieu of a ticket, please consider donating to James’s chosen non-profit: the Violence in Boston, whose mission is to improve the quality of life & life outcomes of individuals from disenfranchised communities by reducing the prevalence of violence and the impact of associated trauma. They work to create safer, healthier, and empowered black and brown communities.

Sponsored by Sounds of Stow; Performed Oct 25, 2020

PROGRAM:

“Lift Every Voice And Sing”, Johnson Brothers, arr. James Dargan;

“I, Too”–Margaret Bonds;

“Life and Death”–Samuel Coleridge-Taylor;

“The Negro Speaks Of Rivers”–Bonds;

“Dream Variation”–Bonds;

“Come Sunday” – Duke Ellington, arr. Dargan;

“Andante from Sonata in E minor”–Florence Price;

“Here’s One” -William Grant Still;

“Dreamkeepers Suite”–Dargan:

“Dreamkeepers”, ” Dreams”, “Sun Song”,

“Minstrel Man” (Bonds);

“My People”;

“blessing the boats” – Dargan;

“Deep River” – Moses Hogan;

“The Promise” – Tracy Chapman, arr. Dargan;

“Boxes are silly, in art, in life, and especially in music: we realize this not only by crossing boundaries (between genres, socially constructed racial groups, etc.), but also by exploring within the boxes, to see how little they actually hold. Since there are common threads between so many different kinds of music, a box like ‘Black music’ holds such infinite variety as to render the label meaningless, and the pieces in this program are just a taste of the different voices of musical Blackness.

The Johnson Brothers (James Weldon, 1871-1938, and John Rosamund, 1873-1954), were taught to love literature and music by their mother (who was a teacher and musician), and together, they produced operettas, musicals, and , including Lift Every Voice And Sing, also known as the Negro National Anthem. James, a poet, wrote the words, and John, a singer and composer, wrote the music.

Florence Beatrice Price (1887-1953) and Margaret Allison Bonds (1913-1972) were teacher and student, and whole programs could easily be devoted to their fascinating relationship: since their careers overlapped greatly, they sometimes found themselves pitted against each other for some of the scanty opportunities available to Black women in the US. At one point, Price moved in with Bonds, Bonds introduced Price to Langston Hughes and Marian Anderson, and both composers subsequently set Hughes’ poetry and wrote for Anderson. The mothers of Price and Bonds were music teachers.

The English composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912) is the lone non-American in this program, though his father was a descendant of Africans enslaved in the U.S. During his short life, Coleridge-Taylor (named after the famed English poet Samuel Taylor-Coleridge) was most well known for his cantata “Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast”, which, after its premiere in 1898, rivaled the popularity of Mendelssohn’s “Elijah” and Handel’s “Messiah” in the U.K.

Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899-1974) was the son of not one, but two pianists, one of whom loved parlour songs, and the other one of whom preferred operatic arias. Because of his innate elegance, Ellington became known as Duke while still a young boy; as an adult, he refused to let his artistic taste be limited by arcane ideas of form or genre. “Come Sunday” is the fourth movement of one of Ellington’s jazz suites for orchestra, called “Black, Brown, and Beige”.

William Grant Still (1895-1978, known as the Dean of Afro-American composers) and I go way back, to when I was eleven years old: the university at which my father taught held a symposium in honour of Still, and his spiritual “Here’s One” became a favourite of mine, in Still’s violin and piano arrangement; I get to sing the original for you, tonight. Still’s parents were both teachers, and his father was a musician.

I wrote my Dreamkeeper songs because I needed teaching material: my third and fourth graders needed some examples of different kinds of vocal text setting, and diverse options of piano part textures, and since James Mercer Langston Hughes (1902-1967) wrote his poetry collection “The Dreamkeepers” for children, it turned out to fit the needs of my students very well. I drew from Schubert, Satie, blues, Mahler, and spirituals when writing these songs, and I kept the piano parts simple, because of the general absence of high quality pianos in the Boston public school system.

“blessing the boats” is the eponymous poem in a collection of Lucille Clifton’s poetry spanning 1988-2000, and even that output is a fraction of a poetic career full of gems, written with scriptural assurance. Do yourself a favour and read all of Clifton’s work. I wrote my setting of “blessing the boats” as a musical recitation, trying to mirror the affect of Clifton’s lines in the piano part, while trying to keep the vocal line true to the poem’s spoken rhythms.

Moses Hogan (1957-2003), is very well known for his choral arrangements of spirituals, and is another one of the many composers on this program whose musical roots were planted by family musical engagement, as well as in the Black church: his father sang bass in their church choir, and his uncle was the same church’s Minister of Music. In his brief life, Hogan wrote over seventy compositions, all of them spiritual or hymn arrangements.

The highly decorated singer-songwriter Tracy Chapman (born 1964), got her first instrument, a ukulele, from her mother, when Tracy was three, and Tracy began playing the guitar and writing songs around eight years old. While studying at Tufts University, Chapman busked around Cambridge, Massachusetts, and after college, she became one of the few Black artists in the folk music scene, and one of that genre’s absolute stars. Chapman included “The Promise” in her fourth studio album, and its words and Chapman’s fearless voice have inspired me since college.” — James Dargan

Contact us for more info.